From the moment I heard Luciano Pavarotti perform “Nessun Dorma,” I was hooked. I had not

become an opera fan, as much as a Pavarotti fan, but it meant that my first official foray into the genre was Giacomo Puccini’s Turandot.

I listened to his music for years before I understood its meaning. Even being ignorant of the

language, I felt the passion in his voice. It wasn’t until Morgan Freeman’s character, Red, in “The Shawshank Redemption” said in his own legendary voice, “I have no idea to this day what those two Italian ladies were singing about. Truth is, I don’t want to know. I like to think they were singing about something so beautiful it can’t be expressed in words and makes your heart ache because of it.” That is how Pavarotti feels to my ears and heart.

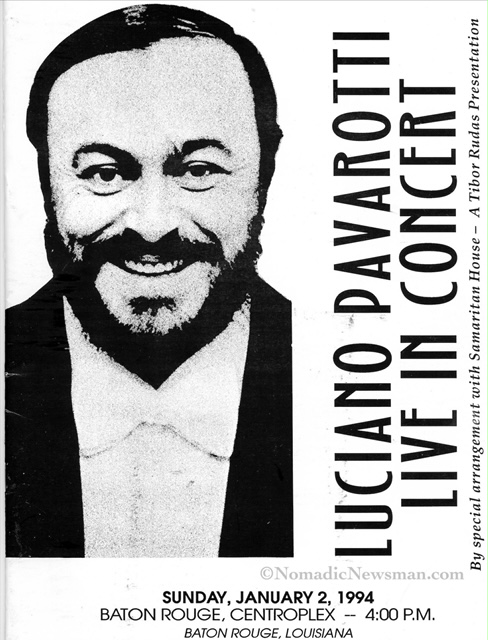

Pavarotti performs in Baton Rouge

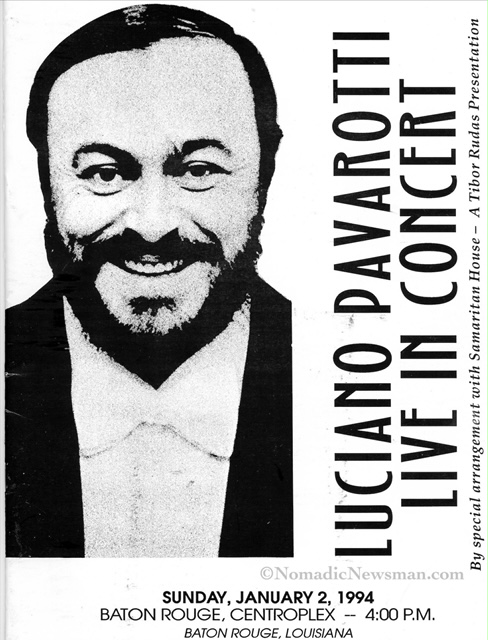

While living on the Gulf Coast in 1993, I learned that Pavarotti was going to perform in Baton Rouge. “The King of High Cs” was doing a show to help raise funds for a Louisiana housing charity.

Paying top dollar for Pavarotti LIVE

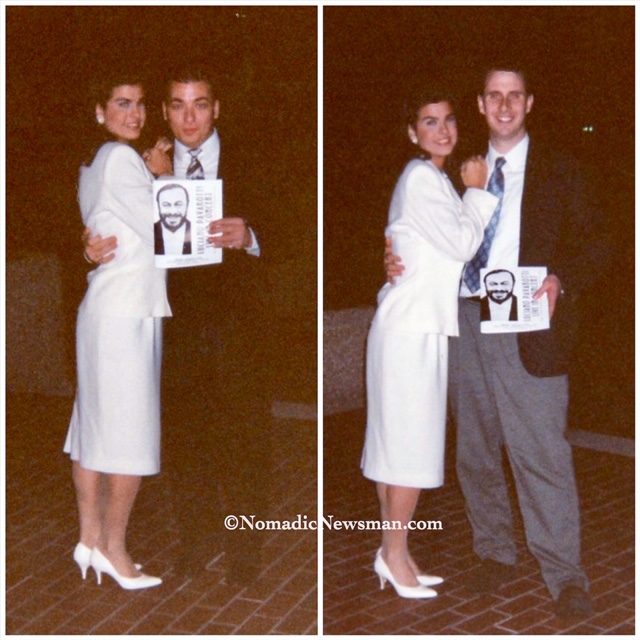

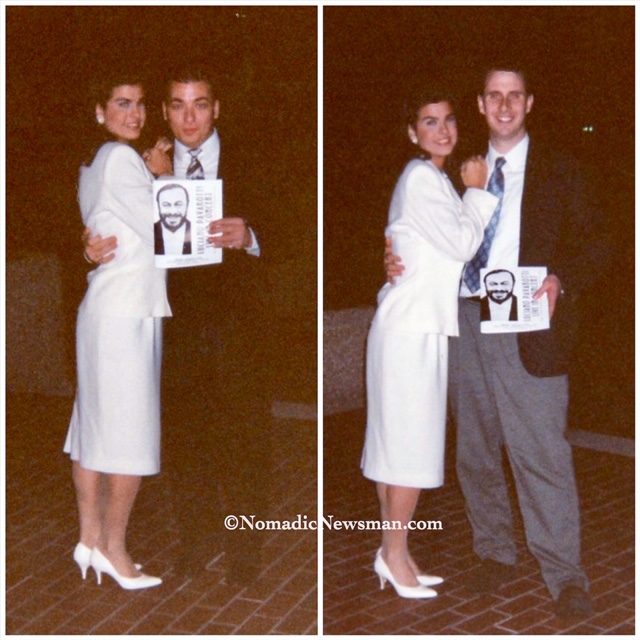

As soon as tickets were on sale, I went to a record store in the mall (this was pre-internet) to buy three tickets; I ordered the most expensive seats money could buy. They were $175 each. I got one for my girlfriend, one for me, and one for my best friend, Frank Lee. The reason I spent my hard-earned radio DJ money on such expensive tickets ($175 each – about $310 each in 2020 money) was that I felt this would likely be the only time we’d get so close to greatness.

On 4 January 1994, we headed to Baton Rouge, where the real-life Pavarotti adventure begins. We arrived at the Riverside Centroplex Arena (now called Raising Cane’s River Center Arena).

Our seats were in an elevated section with a decent side view of the stage. The seats weren’t

fantastic, but they were close and unobstructed.

Sneaking into the front row

Pavarotti came out on stage and began belting out some of his most famous arias. Our seats were to his 10:00 position, and we enjoyed it immensely. I was distracted by three empty front row seats on the floor. I told my concert partners that if the seats remained empty for the first half of the concert, we would move to them at intermission. My plan was met with fear and resistance, as they worried we’d get tossed out of this magnificent event. I told them I needed their support for such a bold move. They gave me their blessing and cooperated and we moved to the floor and took the three front-row seats. We were now spitting distance from the greatest opera singer in the world.

As we meandered the crowd of VIPs and dignitaries including then-Governor Edwin Edwards,

attorney F. Lee Bailey, Tibor Rudas (creator of The Three Tenors) and a host of other

luminaries, I met the organizer of the show. Ambassador Lil Barrow-Veal was the head of a non-profit agency and asked me, in our very brief exchange, if we were coming to the dinner

afterward. I improvised some BS about our desire to attend but that there had been a “mix-up”

regarding the invitations. I don’t know how I just pulled that cockamamie story out of my

“arsenal,” especially since we knew nothing about any sort of afterparty. She asked how many of us would be there. I said, “three” and pointed out my other two mates. She said, “Find me after the show and I’ll get you in.”

During the second half of Pavarotti’s concert, we could hardly contain ourselves with the knowledge that we would be going to some event with the legend. My friends did a good job of tamping down expectations, saying she was going to ghost us the moment the show ended. I was ready for that but still hopeful.

After the show, Ms. Veal was hobnobbing with the VIPs and my friends and I clung to her as best I could. We were hungry strays looking for any Pavarotti snacks she may throw our way.

She moved through the crowd with an entourage of organizers and others and we made it

through every security checkpoint before approaching an escalator. We rode up the moving stairs and arrived at a set of ballroom doors, where the only people being admitted had gold lanyards around their necks. We had none.

She passed through security and we thought we’d had a good run and were totally ready to abandon the soiree with the joy of having seen Pavarotti in concert. In all the madness, Ms. Veal turned and extended three fingers on her elegant hand, waiving us into the private room. We took a seat at a large round table that was positioned about 10 yards away from the head table with name placards marking the seats for Pavarotti and his guests.

As the server brought our salads, I asked if she would bring me get a side of blue cheese dressing. She said it was not possible and the vinaigrette was all they were serving. As the server left, a woman sitting at the opposite side of the table said with mocking disdain, “You’d think at a thousand dollars a plate, we could get whichever dressing we want.” We laughed, but inside I began a sweaty panic, thinking that sometime during the event or thereafter they would come to me for $3,000 to cover our three dinners. That’s a lot of dishwashing, even for three interlopers.

The maestro entered to a standing ovation along with Governor Edwards, F. Lee Bailey, Mr. Rudas, and some other VIPs. They all took their seats at the long table, à la the Last Supper.

A few times during the meal, Pavarotti looked over at my girlfriend and made eyes with her. I

normally would have been a bit jealous. Instead, I felt as honored as she.

When the dinner ended, we all were invited to meet and shake hands with Pavarotti. Somewhere along the way and just a few people in line, organizers stopped the meetings, made apologies, and Pavarotti and friends left. We pilfered anything we could from the table. I wanted Pavarotti’s name placard, but it had already been claimed. We still left Louisiana elated; Three people could not have had a better experience.

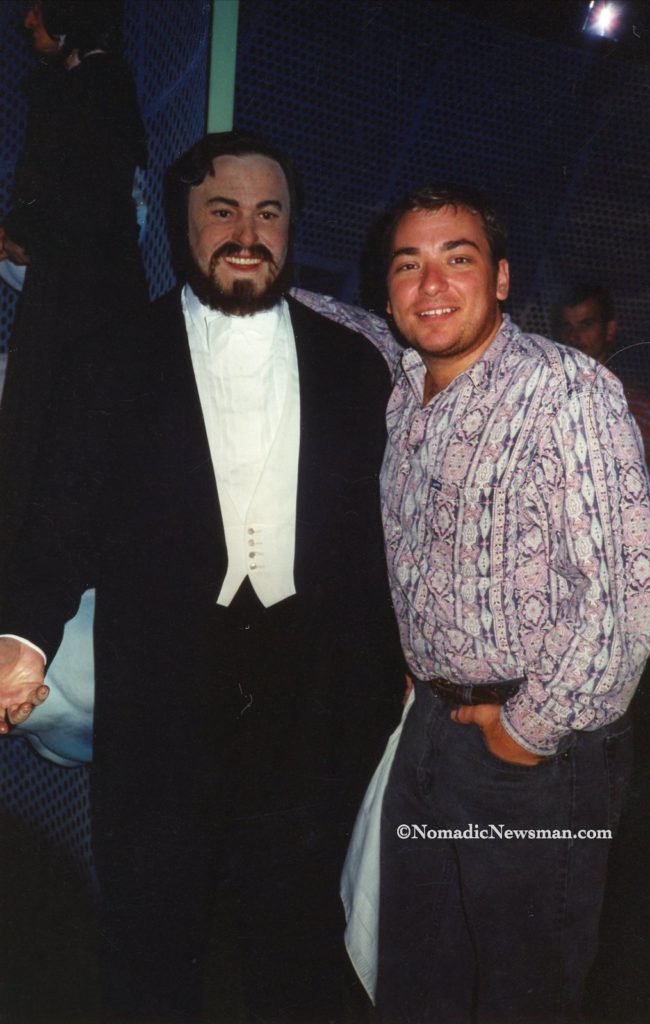

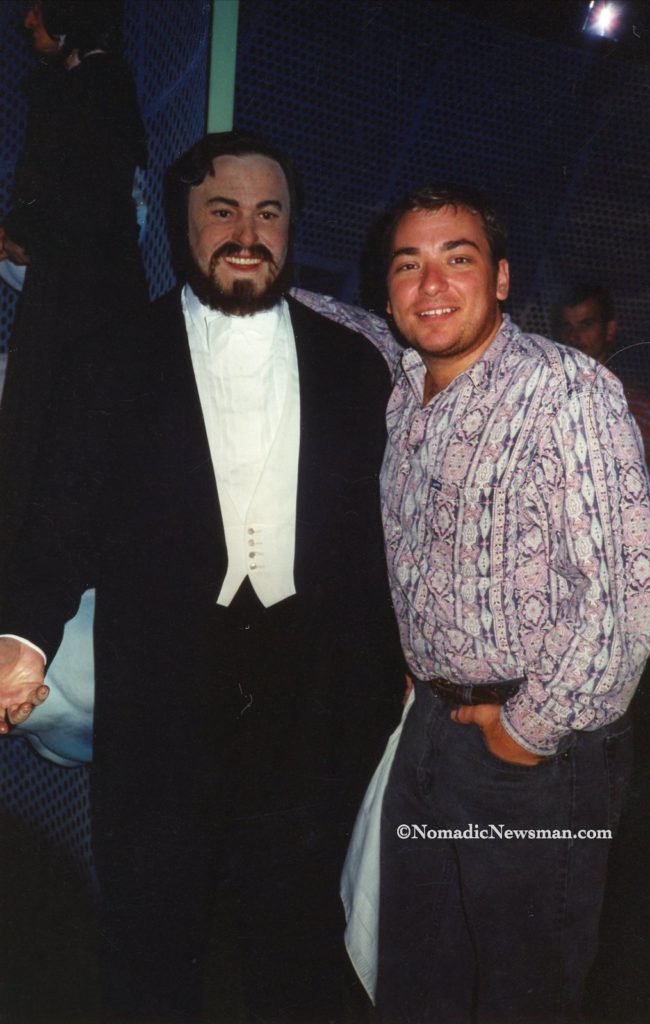

Fast forward to 1998. In Amsterdam, at Madame Tussauds, I posed with the wax figure of Pavarotti. I couldn’t wait to share it with my Baton Rouge concert partners. I thought it would be a nice way to wrap up my amazing Pavarotti experience. It was not the end…at all.

Getting the “impossible” interview

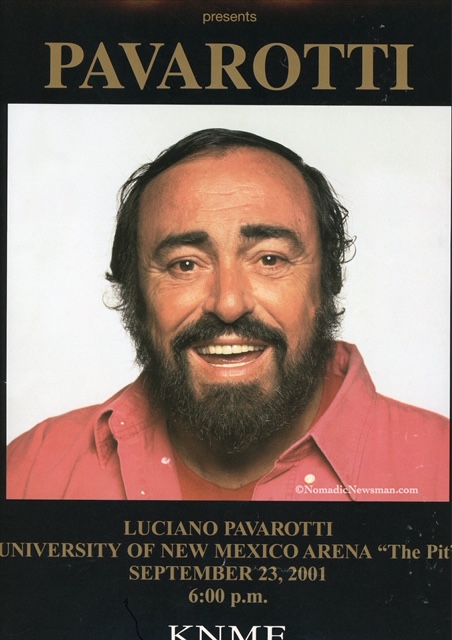

In 2001, while working at the NBC affiliate in Montgomery, Alabama, I got word that Pavarotti was coming to Birmingham, for his first and only concert in Alabama. I immediately started shaking the trees to try to work out an interview. This was “impossible,” as Pavarotti does interviews with Barbara Walters, Diane Sawyer, Mike Wallace, and Oprah. He doesn’t do interviews with Joey Parker or any locals.

When I started my dialogue with Pavarotti’s people, I started off by saying, “Please do not say ‘no’ until hearing me out.” I told them of my Baton Rouge experience and explained that I was a hardcore (not a Johnny-come-lately) fan. I even bribed them with Alabama BBQ I had shipped on dry ice to their New York City offices. The shipping cost three times as much as the BBQ.

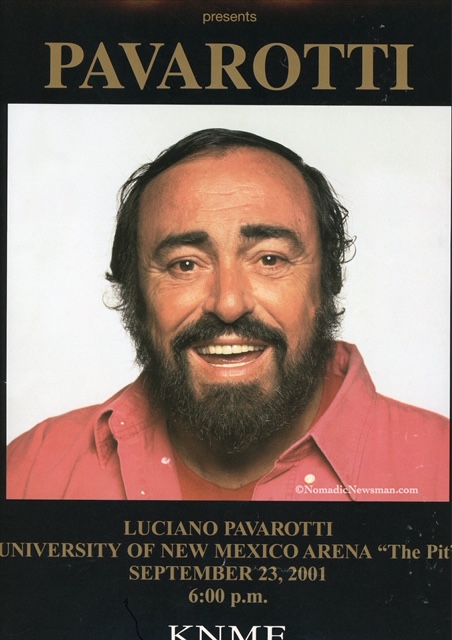

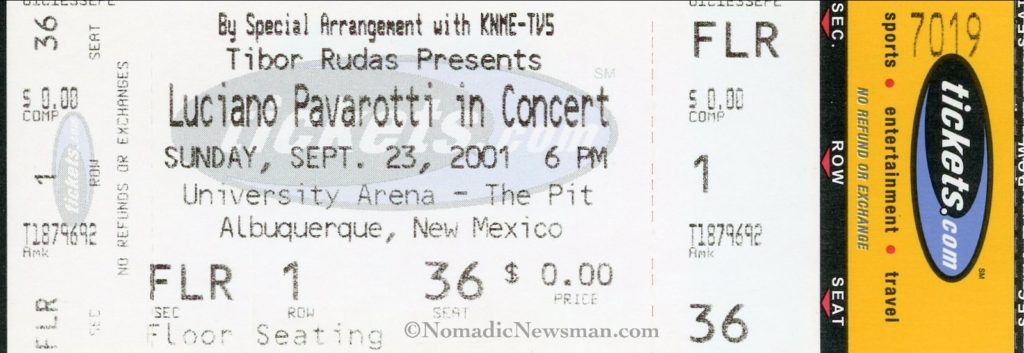

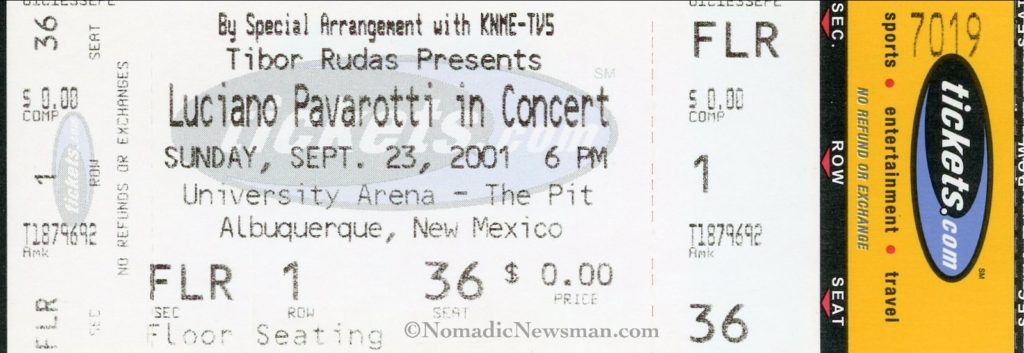

Eventually, one of his people said Pavarotti would be performing shortly before his Alabama concert in Albuquerque, New Mexico. They asked if I would be willing to travel that far to do an interview to promote the Birmingham concert in advance. I distinctly remember my answer: “I would go to Hell to interview Luciano Pavarotti!”

After a big laugh and a thank you for the “delicious BBQ,” we eventually set plans for an interview in Albuquerque.

Finding familiarity in a time of terror

On a beautiful September morning, I watched along with the rest of the world as our nation came under attack. The last thing on my mind during the 9-11 terrorist attacks, was my interview with Pavarotti. Much like the current COVID-19 crisis, the nation was turned upside-down.

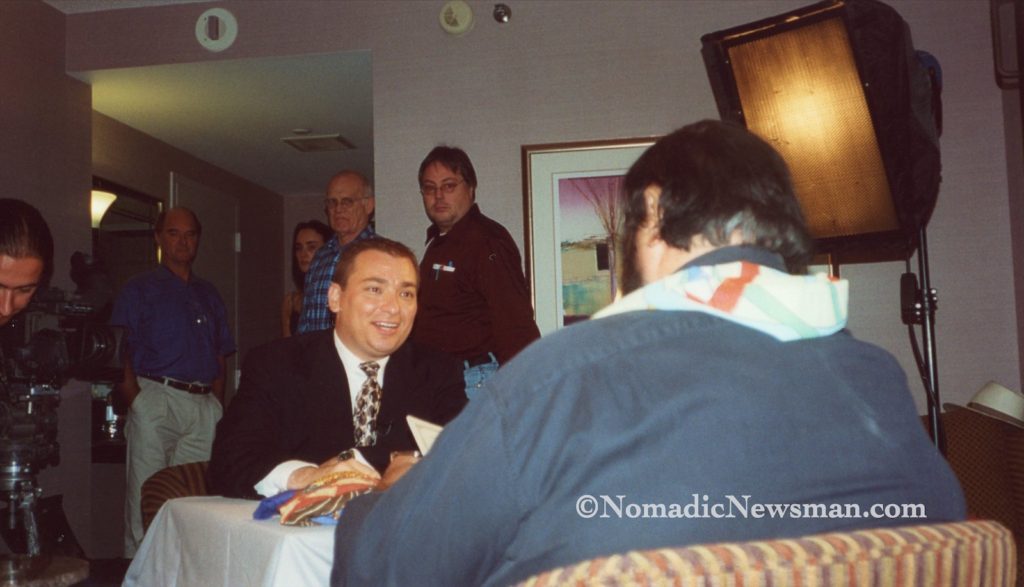

When I got to Albuquerque, I told my production crew from KNME-TV what I was thinking for months leading up to the show, that the interview was very likely not going to happen. Legend has it that he has had two former U.S. presidents in his audience and canceled the show because of a throat tickle. This was weeks after 9-11 and Pavarotti was out of his normal artistic element and in the dry climate of New Mexico.

The hotel arranged a room on the same floor as Pavarotti’s suite. We set up at the appointed time, met with his people, and began the wait. I shared my feelings with the crew about

envisioning Pavarotti in his suite, looking at his agenda and saying, “Who the hell is this guy?

And, why am I doing a local television interview? Cancel it!”

As I peeked out of our room down the hall to Pavarotti’s, we waited 15, 30, and then 45 minutes. When we hit the one-hour mark, and I was accepting the reality it was not going to

happen. I looked out for what I figured would be the last time. There was movement. People

were gathering outside his room, and then it happened. Luciano Pavarotti stepped out of his room and was on his way to MY room.

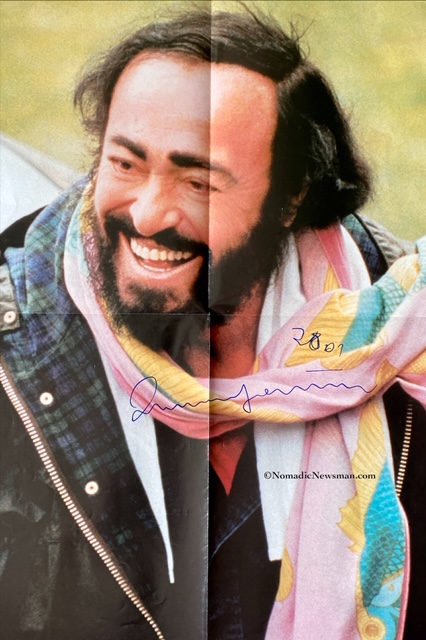

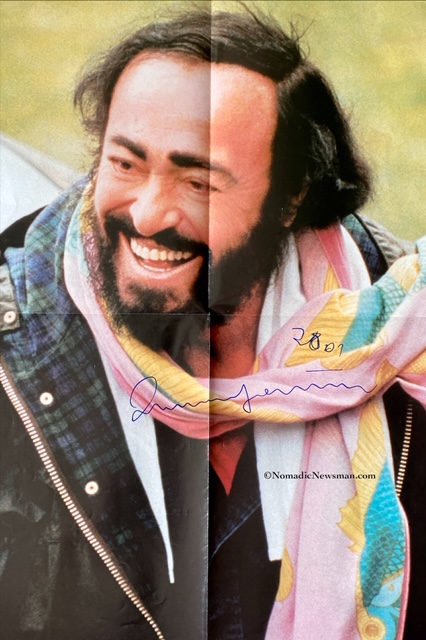

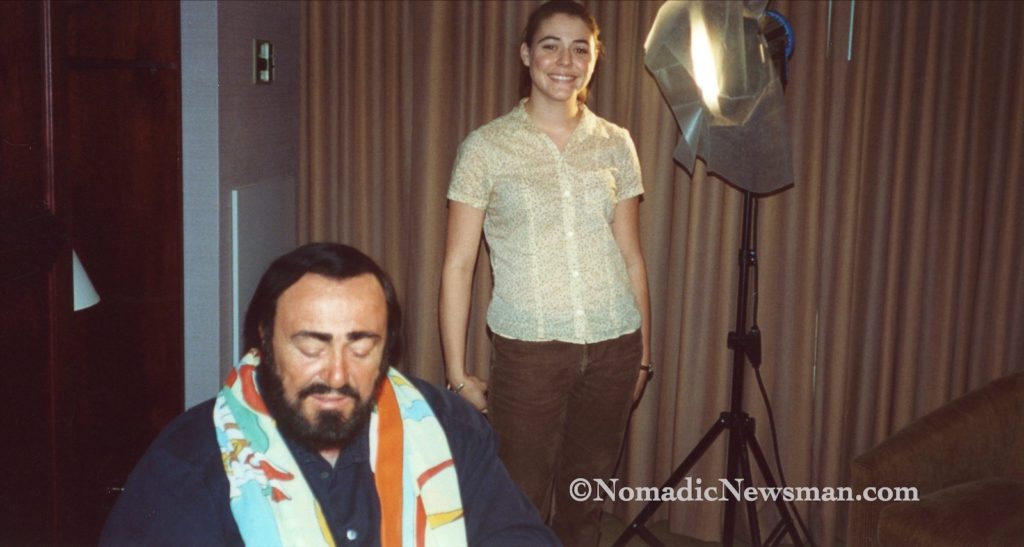

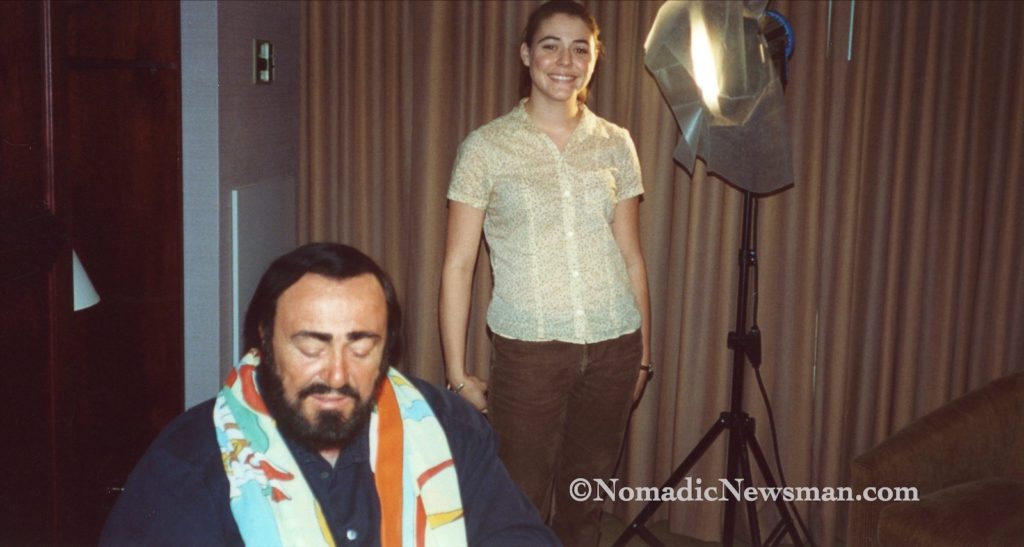

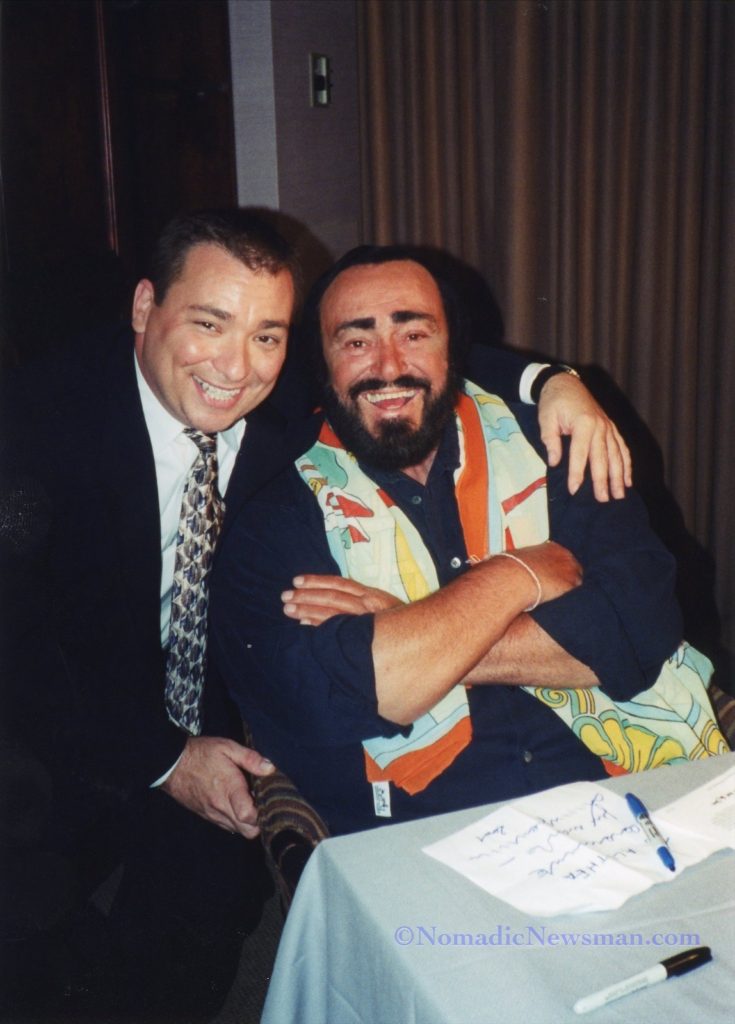

We met and kindly shook hands. We got seated. As the intern, Amber McClarin, was attaching his microphone to Pavarotti’s signature silk scarf, I couldn’t help but fawn. As I was explaining to him how he single-handedly “turned me on” to opera making me a fan decades before our meeting, he was eying Amber. She was aware of Pavarotti’s wandering eye and flirtatious behavior and took it in stride. I think she was even amused.

Pavarotti sniffs my watch

While the photographer, Manuel Machuko, was adjusting his lighting, Pavarotti noticed my Hublot watch. He pointed and said with his thick Italian accent, “Hublot?” I hesitated because I didn’t understand his question. When it hit me, I confirmed it is a Hublot watch. In the excitement of the moment, I opened the deployment clasp of the watch and handed it to him. He took it from my hand and drew the watch to his nose to sniff it. This was a snapshot of a memory that I’ll never forget. I wondered to myself, “What series of events has led to my being in a hotel room with opera legend Luciano Pavarotti sniffing my watch?” I still get a laugh out of that moment. In reality, he was pointing out how the rubber strap doesn’t emit the funky smell of a men’s leather watch strap.

The interview got underway. I was moved by his relaxed demeanor and at how agreeable and personable he was. It was going well until I asked him how the events of 9-11 affected him. His eyes turned red and welled with tears and he took a deep breath. I knew I had just blown this interview, I knew I had lost Pavarotti and his people were about to step in and stop the interview they felt was getting perhaps too personal. After a pause, he sighed and answered the question with passion. He said the terror attacks were “the death of my soul.”

We rebounded and spent the better part of an hour together. After the interview, I wanted to get one quick reverse shot while he was there. For people who are not in television, this is where we put the camera to the rear side of the subject for cutaways, reaction shots and editing purposes. I was afraid to ask him so the Manuel knew from my rehearsed look to quickly get the reverse shot. Pavarotti noticed and was patient. We chatted, and I showed him the picture of me posing with his wax replica. He asked if this was from London or Paris. I told him it was from Amsterdam. He had no idea “he” was on display in Holland. I told him I thought this was as close as I would ever get to meeting him and also shared our Baton

Rouge experience.

Not only did we blow out the 15-minute time limit, after an hour together we were still having a pleasant time. So pleasant in fact, Pavarotti invited me to play poker with him that evening, and soon to Modena, Italy, so he could cook a meal for me. I told him I like cooking and will treat him, but he said, “I do the cooking. You eat!”

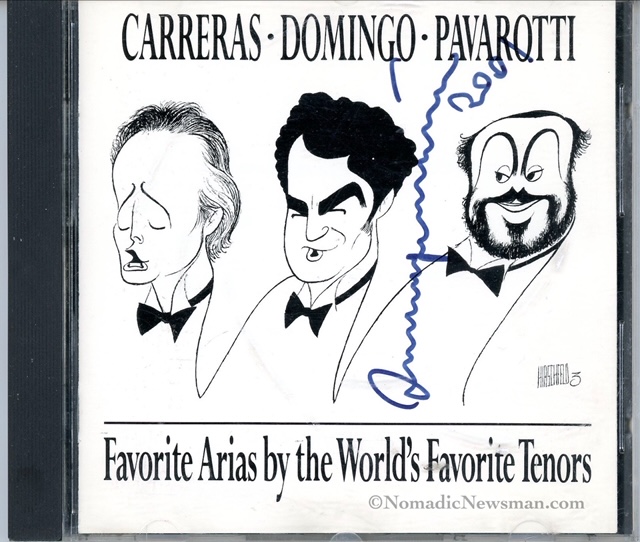

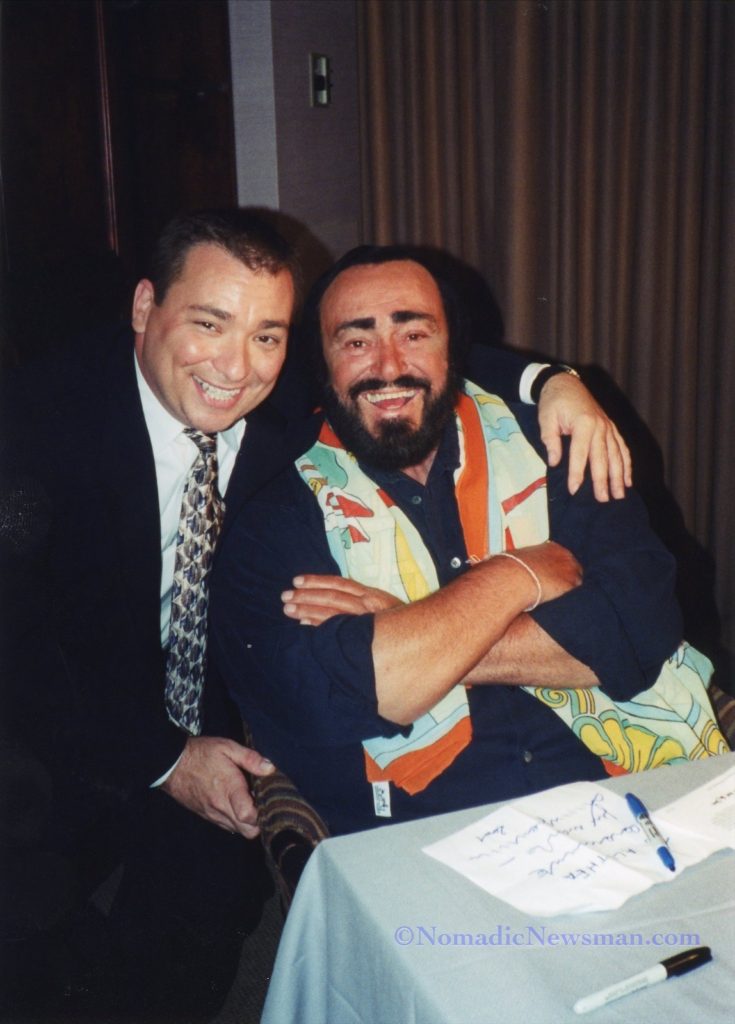

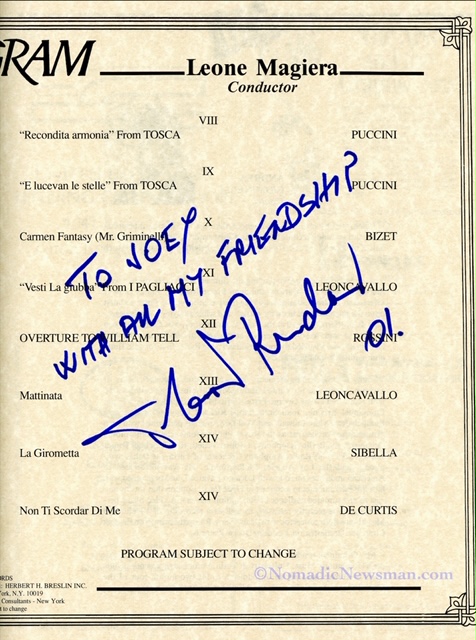

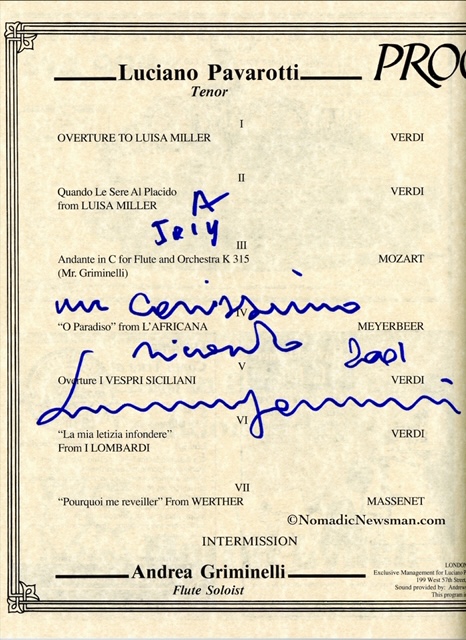

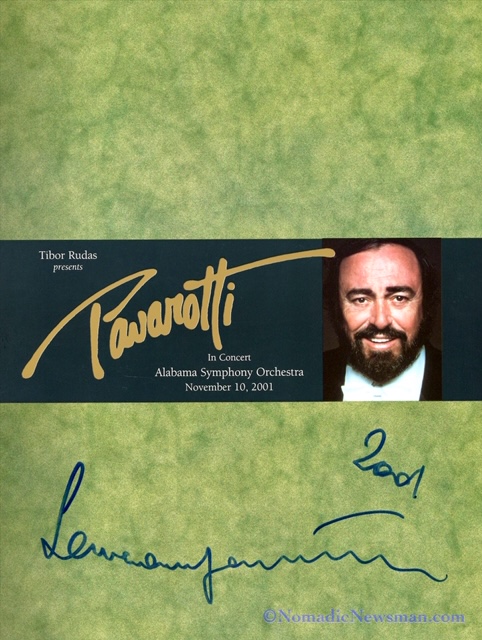

We finished the interview, he posed with me and the crew for pictures, signed autographs

and recorded some promotional pieces for A&E. That’s when A&E really meant Arts and

Entertainment. It was also when TLC actually meant The Learning Channel.

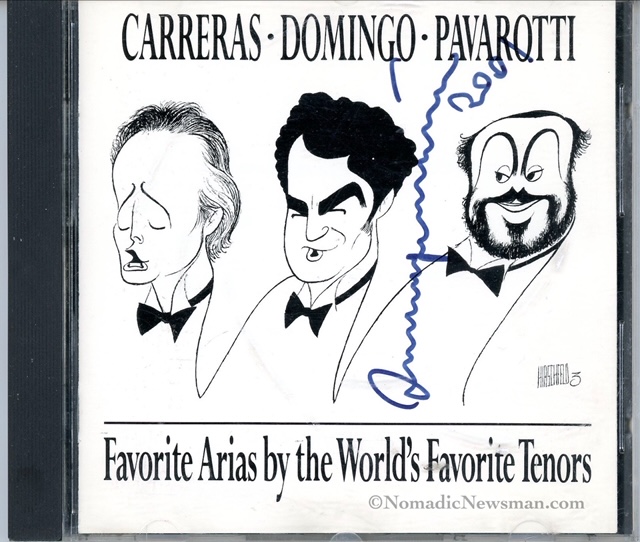

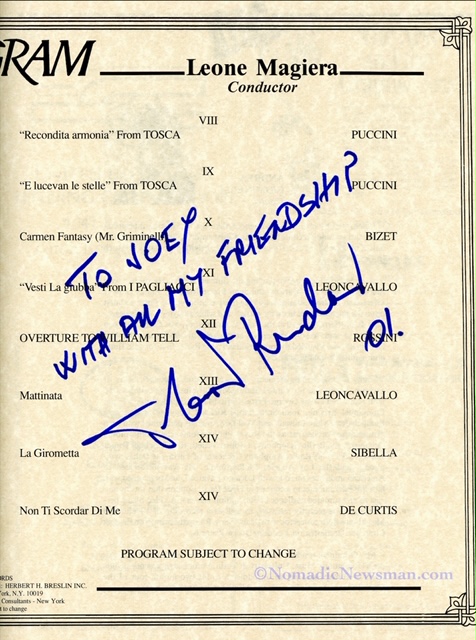

BONUS: Visiting with legendary promoter Tibor Rudas

As a bonus, I was able to have an interview with the show’s producer, Tibor Rudas, often referred to as “the George Martin of opera music.” The once prisoner of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in Germany, Mr. Rudas became as important in arranging and producing the Three Tenors (Mr. Pavarotti, Plácido Domingo and José Carreras), as Mr. Martin was to The Beatles.

When we finished, Pavarotti walked by my “football.” That is my makeup and prep bag that goes with me everywhere, thus “the football.” Aside from my earpiece, makeup, and other necessary things for television work, I had a tin of Altoids. He reached in and grabbed them. He asked if he may have one and I offered him as many as he’d wish. I still have the tin because it potentially has his skin cell DNA inside. I mean that not in a creepy way.

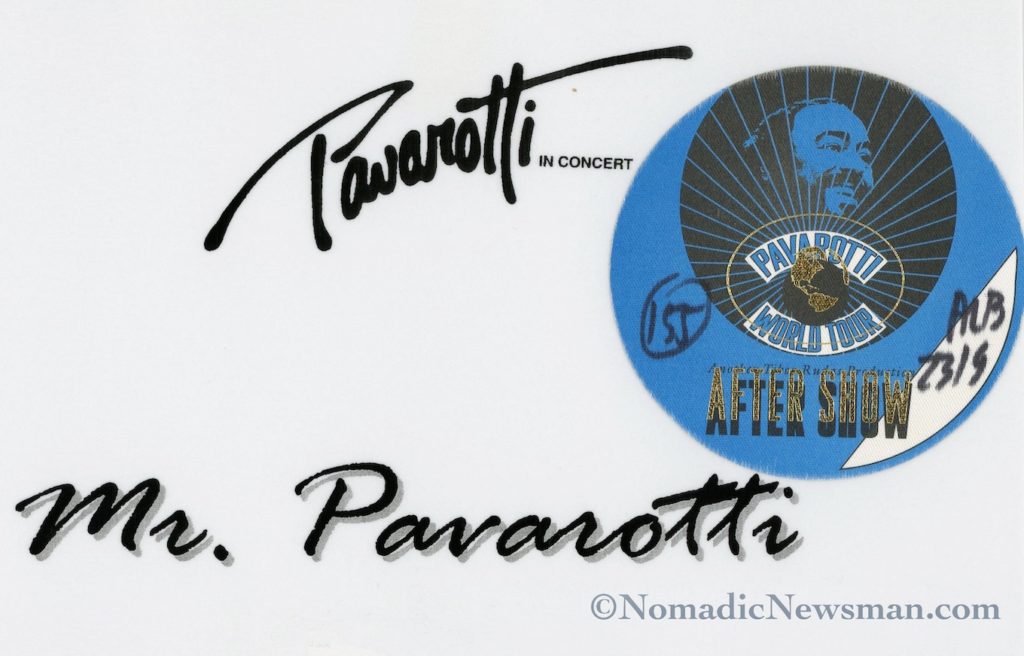

Pavarotti asked if I was going to the show “tomorrow night.” I said we would love to see him perform. He set us up with front row seats. I mean he arranged those prime seats for me, the cameraman, the intern and their significant others, as well as the general manager of the TV station and his wife.

History taught me that money cannot buy front row tickets. If this had been a serious news

interview, I could not accept such a gift. In fact, it was ethically questionable anyway.

The next day, the crew accompanied me as invited guests to what is always a closed rehearsal. After the evening concert, Pavarotti allowed us all to visit him backstage. He did pictures and autographs and joked about BBQ. I was gobsmacked to learn Pavarotti had tasted the Alabama BBQ I sent to New York.

The next day, the crew accompanied me as invited guests to what is always a closed rehearsal.

After shooting for a few minutes, the tour manager kicked us out. As we were leaving, even

though we told him that we had permission to be there, Pavarotti saw us heading out, and yelled my name. He waved us back in, and we continued to shoot with unfettered access. It was remarkable.

After the evening concert, Pavarotti allowed us all to visit him backstage. He allowed pictures, signed autographs, and joked about the BBQ. I was gobsmacked to learn Pavarotti had tasted the Alabama BBQ I sent to New York.

When I got back to my room that night, I called my friend, Frank Lee who was my partner in crime in Baton Rouge, and told him my career was done. Nothing could top this. After the extremely depressing lows of 9-11, I had one of the greatest moments of my life with a musical hero I had admired for so long.

Pavarotti in Alabama

Once again, Pavarotti and his people arranged front row tickets again at his 10 November 2001, concert at the Birmingham Jefferson Civic Center. My guests would include Frank Lee, my girlfriend who was with us in Baton Rouge, and some of our friends. We all enjoyed the show and were granted backstage access again. My friends all got to meet him and get autographs. He did not allow pictures because his leg was troubling him and was bandaged and elevated on a scooter.

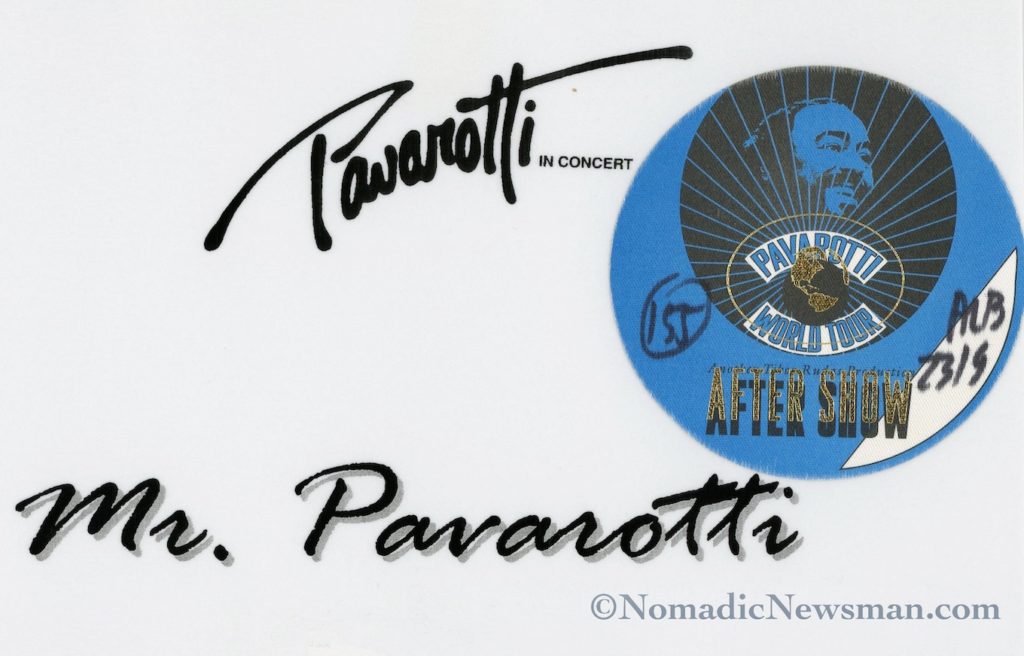

I did score his dressing room door sign. I stuck my backstage pass on it for the scrapbook.

Before we left, his manager mentioned something about the barbecue. Pavarotti made the

connection and asked if I could get him some more of “that delicious barbecue.” I told him I

would try. When we got back in the limousine (we had to treat ourselves for this very special

event), I called Dreamland in Birmingham and asked if we could get an order delivered. They

told me they had shut down the BBQ pits for the night. When I told them it was for Pavarotti and crew, the restaurant manager asked if I could get an autographed picture for the restaurant if they fired up the pits again and delivered to his hotel. If you’ve never been to this iconic BBQ restaurant, Dreamland has celebrity memorabilia decorating the dining room. It’s mostly autographed pictures of sports legends such as Alabama Football football Coach Paul “Bear” Bryant and other sports icons. I told them we had already left the venue but gave him the contact number of Pavarotti’s manager and I paid for the BBQ.

The latter and final years with Pavarotti

Sometime later, some friends and I were headed to see Aerosmith in Birmingham at the same

venue. Arena workers dropped the massive scoreboard onto the stage crushing some of Aerosmith’s equipment and causing the band to cancel the show. I already had tickets and

plans to go to Birmingham, so we continued on. While we were figuring out what we were going to do, I proposed we eat at Dreamland. As we walked to our seats in the restaurant, we noticed something special. Ensconced in a lighted and locked glass case was a picture with the

inscription, “The best BBQ ever…Luciano Pavarotti.” I had chills and a stupidly huge grin knowing that I was a part of making this happen.

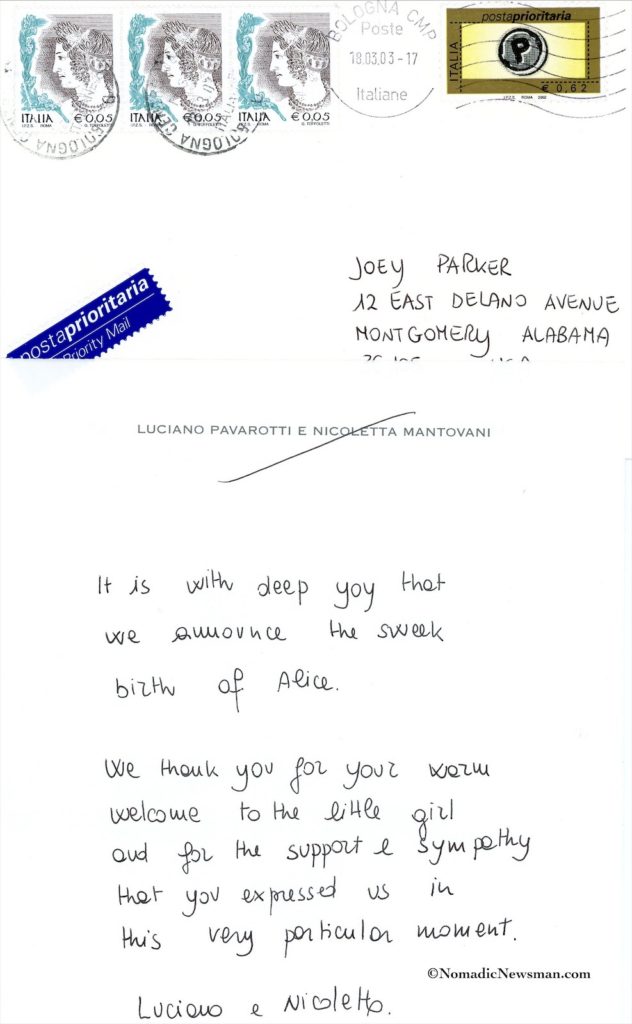

In 2003, I sent a note to Pavarotti’s home Modena, when I learned that his wife, Nicoletta Mantovani had given birth to twins. I congratulated the couple on the birth of daughter, Alice, and sent sympathies regarding the stillbirth of her twin brother, Riccardo. I received a nice thank-you note from “Luciano and Nicoletta.”

In 2007, I learned how serious Pavarotti’s health problems were. I sent him pictures and a letter reminding him of this very long tale and how much he means to me. To this day, I do believe he saw it before he died of pancreatic cancer on 6 September 2007.

When I hear one of his songs or see him on a TV broadcast, all these memories come rushing

back with the force of a pleasant punch to my emotions. His kindness, generosity and passion

still fill me with a joy that’s deeply appreciated.