The usual scorching heat of the Pensacola, Florida summer beat down relentlessly on August 7th, 1987. Little did I know that this date would forever be etched in my memory, not only for its alliteration of eight seven eighty-seven but for the life-altering, harrowing events that were about to unfold.

My mission was to move my show’s television studio set from Pensacola to Mobile, Alabama, for storage. I was with my then-girlfriend, Kristi, and a mutual friend. Little did I know that this seemingly mundane task would plunge us into the depths of danger.

Picking up and loading the set into the back of a pickup truck proved uneventful. The trouble started when we realized the tarpaulin had come loose on one corner, causing the pieces of the large but lightweight set to blow onto I-110 a mere three miles from the trauma center at Baptist Hospital.

Kristi looked at me and asked, “What do you wanna do?” The littering aspect came to mind first. Then I remembered the pieces of the set, some upwards of a square yard each, are made of sturdy but floaty Dow Chemical Board used most often for inflation could cause a serious crash.

I decided we should pull over, stop and retrieve the pieces. We all scrambled to collect the items that once served as a physical manifestation of the first TV show I ever created.

The blistering hot road stretched out behind us with the boards strewn about. We made our individual and random routes through the asphalt arteries, carefully avoiding and dodging traffic.

Kristi pointed to a piece of board 40 yards down the highway and moved toward its direction. I grabbed her Dallas Cowboys football jersey, which would later become a tourniquet and said, “I’ll go get it…it could be dangerous.”

Just as I recovered the board, I saw a car approaching the bend at full interstate speed. It’s still estimated that the vehicle was traveling at 65 mph (105 kph). A terrified Kristi saw it too.

We were waiting for the screeching of tires, but instead, the vehicle and I did the “hallway dance,” simultaneously moving side to side to avoid each other, only to remain on a path of collision. This was a possible dance with death.

While it happened in real-time, in mere seconds, the moment seemed to be slow enough for me to realize every unavoidable moment.

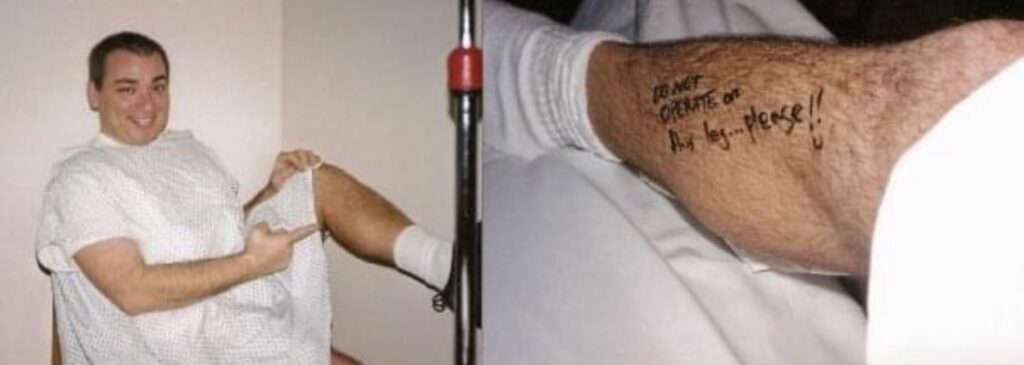

I looked back and realized the car was about to make contact with my left leg while I was in a running position. I tensed up and bit down, bracing for impact. The grill appeared to me as the angry exposed teeth of a monster as it hit my left leg, shearing and tearing a compound fracture of my tibia and fibula.

The estimated 200,000 pounds (91,000 kg) of force threw me onto the hood with my right hand slamming the windshield as if to stop me from going through the glass. It kept me from flying through the windshield and into the car’s cabin.

The shattering tempered glass turned the palm of my hand, as the doctor described, into what looked like “hamburger meat.” My hand was forced down as it punched the dashboard, breaking my wrist and causing compound fractures of the ulna and radius. My body’s impact, the car’s speed and the laws of physics sent me hurtling over the vehicle some 30 feet (10 m) in the air only to fall like a ragdoll to the unwelcoming sizzling skillet of asphalt below.

I remained conscious through the terror of the crash and learned the meaning of “solar plexus syndrome,” or having the wind knocked out of me. Once I regained my breath, I was embarrassed to have fallen so clumsily in front of Kristi. After all, James Bond would have punched through the windshield, slapped the inattentive driver, taken the wheel and saved the day. That thought made me want to stand up, dust myself off and say, “I’m okay.” I was not “okay.”

For a discombobulating moment, I feared Kristi and perhaps others were hurt as well. She reassured me that was not the case while using her jersey to tie off my blood flow hastily. The unrealized skills of a future nurse and the daughter of a practicing nurse kicked in. Otherwise, it would have been more than the four liters of AB-negative blood that soaked into the interstate’s pores that day. I’m certain my life would be drained before first responders could arrive. Thank you, Kristi. I still owe you.

Not realizing the extent of my injuries, I didn’t think I was anywhere close to death. I thought I might be treated in the hospital and released that same Friday night.

I told Kristi I had glass in my mouth, but upon closer inspection, she and I realized it was not glass but tiny shards of my own teeth caused by biting down during the impact.

Despite the hospital’s close proximity, emergency responders decided to collect me in a medical helicopter rather than a road ambulance during heavy traffic. Fortunately, Baptist LifeFlight had been established one decade before this crash. It was the first aeromedical helicopter program in Florida and only the third in the United States.

Kristi spoke words of encouragement while keeping me alert and conscious while paramedics built a tent over my body to avoid further injuries.

Soon they loaded me into the chopper, where a man leaned over to inspect my chart and injuries. “19-year-old male pedestrian hit by a vehicle at a high rate of speed. Compound fractures of the ulna, radius, tibia and fibula, various lacerations, contusions and extreme thermal burns…unknown internals,” he communicated to the trauma center. I muffled indistinctly underneath the oxygen mask, and he pulled it away from my nose and mouth to ask me to repeat what I said. “There are no internal injuries,” I told him. He laughed as he radioed back to the hospital, “Patient advises there are no internal injuries.”

He asked me who I was. I told him. He asked me who the president was. I said, “Ronald Reagan.” I could not, however, accurately answer what day it was or the time of day.

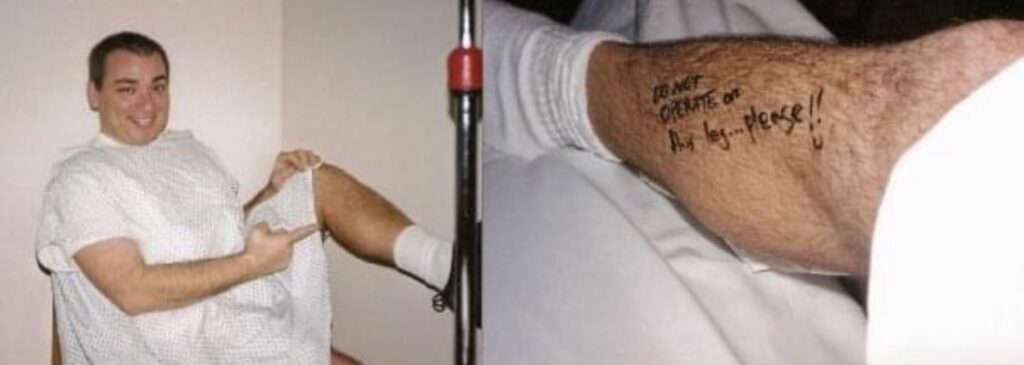

Although I was certainly uncomfortable, it wasn’t until I was being prepped for emergency surgery that the pain started. They refused pain meds because of the procedures that were to follow, and I begged for water, even for a sip. I was refused for the same reason. Kristi was still by my side with a small plastic container of water and a gauze pad to keep my burnt lips moistened. I told her she’d give me a sip from the container if she loved me. She had a moment of laughter through her hours of shock and tears.

I awoke in the recovery room with the harsh fluorescent light bathing my eyes with its flickering mercury poisons.

They eventually rolled me into a room where my once estranged mother would assist me in recovery. It was a kind and healing gesture in multiple ways, but it caused tensions among Kristi, her family and my foster family. That’s another story altogether.

The doctors, nurses, specialists and attendants were in and out of the room all day, every day, examining me, running tests and changing my sheets. The changing of the sheets was an excruciating process as more than 60 percent of my body was covered in asphalt burns. The sheets appeared covered in burnt cornflakes at each change.

The worst part of the day was when they’d bring in the arterial stick. I distinctly remember during one visit with the nurse bringing the now familiar “caddy of pain.” I started to cry like a child. It felt as if they were driving the needle into my wrist bone.

I didn’t have much time to recover, as I had trouble breathing. I eventually couldn’t breathe on my own and was taken to ICU.

As my blood oxygen level dropped to 30 from the normal healthy level of 95 to 100, it was realized that I had suffered a pulmonary embolism.

My grandfather from Atlanta was in the room during one of my lucid moments. We only talked on the phone a few times a year, and visiting in person was even rarer still. It was a joy to see him, but that’s really the first time I knew I was in danger of death. He was not a sentimental man, and I thought he wouldn’t see the point in traveling five hours for a mere hospital visit.

I was later told the doctors said the family may need to consider funeral arrangements because nothing other than oxygen treatment could be done. “It’s now up to the patient.” Sometimes they recover, but it did not look good at my level of hypoxia and hypoxemia.

Days turned into weeks as I fought a grueling battle against pain and despair. Physical therapy became a daily ritual, each step forward an arduous triumph over the injuries ravaging my body.

Months turned into years as my body slowly healed for the most part, leaving behind scars that told a story of survival. The road to recovery has been long, arduous, and fraught with setbacks, addiction issues, pain and distractions.

During the depths of darkness, I turned to a god, resented and even hated a god and eventually decided that no god was responsible for my tragedy or seemingly miraculous survival.

The reasons I survived and am alive to write this 36 years later are Kristi, the first responders, the doctors, nurses, technicians, other medical experts, science and my surprising will to continue.

I have not feared death from then on. In fact, I used to jokingly say that I cannot be killed by conventional methods. Although I am still fearless of the end, I am aware that I, like all of us, have an unavoidable date with the Grim Reaper. It just wasn’t 8.7.87.

“A brush with death always helps us to live our lives better.” – Paulo Coelho